The evolution and future of cell therapy in Viet Nam: A 30-year journey from pioneering steps to national strategy (1995-2025)

- VNUHCM-US Stem Cell Institute, Univesity of Science, Viet Nam National University Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam

Abstract

Over the past three decades, Viet Nam has advanced from performing its first tentative cell-therapy procedure to designating the field as a national strategic technology. This review reconstructs that trajectory, analysing the scientific, clinical, regulatory, and infrastructural milestones that have shaped the Vietnamese experience. The narrative opens with the inaugural successful haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in 1995, an achievement that galvanised nationwide interest and built local capacity. It then highlights the creation of dedicated research centres—most notably the Laboratory of Stem Cell Research and Application (now the VNUHCM–US Stem Cell Institute) in 2007—which precipitated a surge of preclinical studies on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) tailored to prevalent domestic diseases. Subsequent clinical translation encompassed the expansion of HSCT programmes and the pioneering use of MSCs to treat knee osteoarthritis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A further milestone was the development and clinical adoption of Autologous Immune Enhancement Therapy (AIET) for solid tumours, exemplifying advanced translational research. In parallel, the award of international AABB accreditation for cellular-therapy services in 2023 affirmed Viet Nam’s adherence to global quality standards. These scientific gains unfolded within an evolving regulatory environment that culminated in the 2025 designation of cell therapy as a National Strategic Technology. Despite these successes, outstanding challenges include finalising comprehensive regulations, conducting large-scale clinical trials, reducing costs, and ensuring equitable access. Through targeted international collaboration, sustained investment, and continued integration of research, clinical practice, cell banking, and quality-assurance infrastructures, Viet Nam is poised to emerge as a major regional contributor to the global cell-therapy arena. Its 30-year experience thus provides an instructive model of biomedical innovation in a resource-constrained setting.

Introduction

The 21st century has witnessed a paradigm shift in medicine, moving beyond conventional pharmacology and surgery towards targeted, biologically derived therapeutics. Cell therapy—the administration of living cells to repair, replace, or regenerate damaged tissues and modulate immune function—stands at the forefront of this revolution in regenerative medicine and immuno-oncology. Globally, this field has progressed from theoretical concept to clinical reality, exemplified by approved therapies like chimeric antigen receptor T-cells (CAR-T) for blood cancers and extensive research on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for degenerative diseases 1,2,3,4.

For Viet Nam, a nation with a rapidly modernizing healthcare system, a significant burden of both communicable and non-communicable diseases, and an aging population, the promise of cell therapy holds particular resonance. Its potential to address intractable conditions such as cancer, osteoarthritis, spinal cord injuries, and pulmonary diseases aligns with pressing national health priorities. Vietnam’s engagement with this frontier is not a recent phenomenon but the result of a deliberate, thirty-year journey characterized by scientific ambition, strategic international partnership, and incremental policy evolution.

This journey began not with widespread application, but with a single, courageous clinical act. The first successful hematopoietic stem cell transplant in 1995 served as the initial spark, demonstrating technical feasibility and igniting a national endeavor 5. What followed was a complex trajectory involving foundational laboratory research, technology transfer, the establishment of core facilities, pioneering clinical trials, and an ongoing effort to create a coherent regulatory environment. This path mirrors the global evolution of the field while being distinctly shaped by Vietnam’s specific context, resources, and challenges.

The primary objective of this manuscript is to provide a comprehensive synthesis of Vietnam’s 30-year development in cell therapy. We will delineate the key historical phases, from pioneering isolation to strategic integration. This includes examining the preclinical research that built national capacity, documenting the critical clinical trials and therapies that have entered practice, analyzing the evolving regulatory and ethical framework, and discussing persistent hurdles and future opportunities. By illuminating this unique narrative, we aim to highlight Vietnam’s emerging role in the global biomedical community and offer insights for other nations navigating similar developmental paths in advanced therapy.

The historical trajectory: Three decades of development

Vietnam’s cell therapy journey can be segmented into distinct, overlapping phases that reflect its growth from an isolated clinical achievement to an integrated component of national health and science policy.

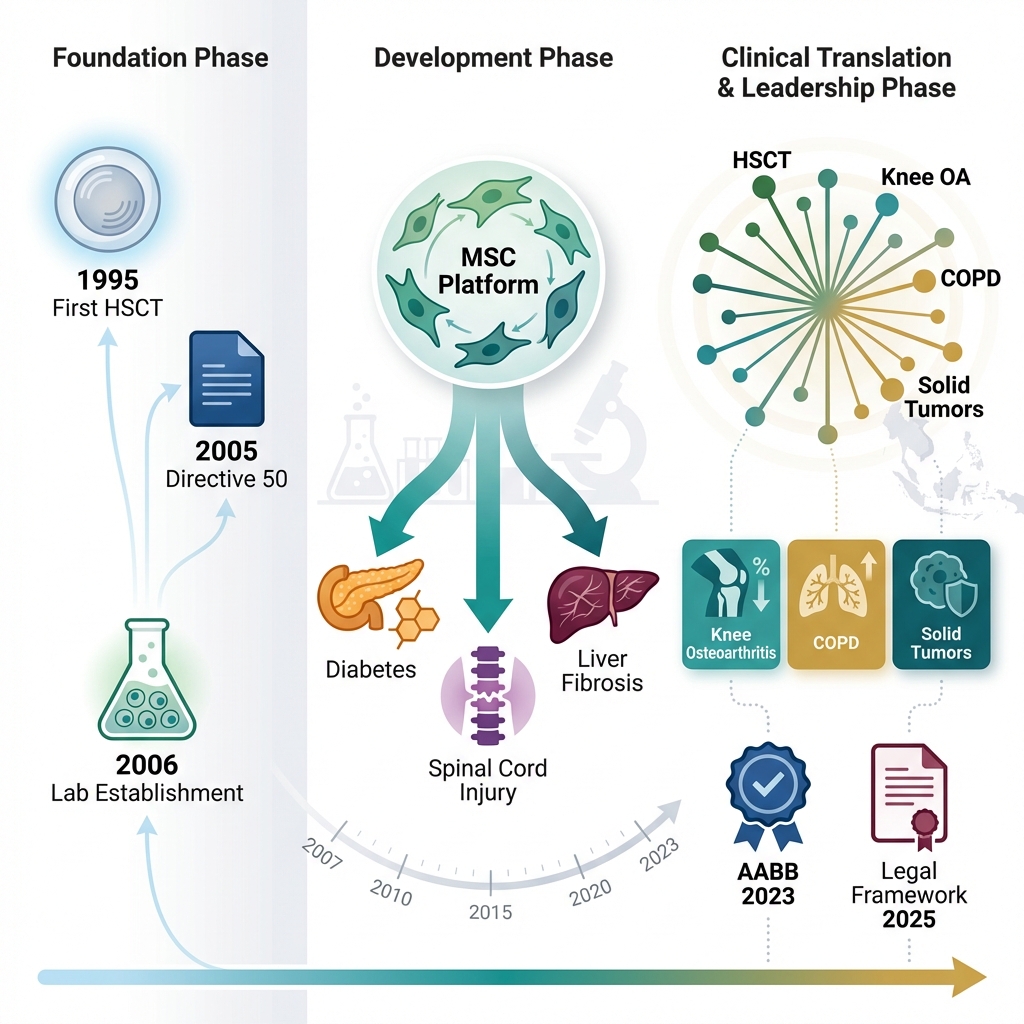

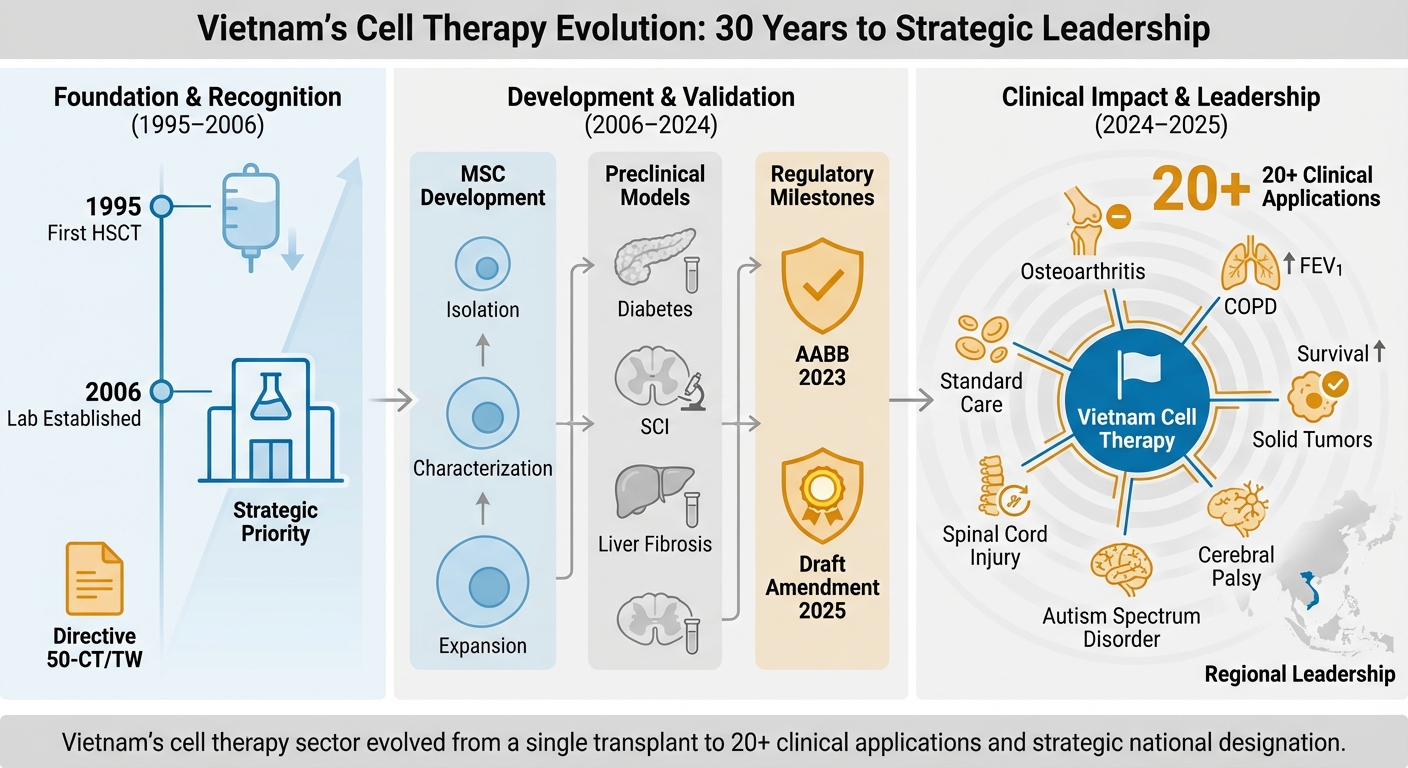

Vietnam’s Cell Therapy Evolution: 30 Years to Strategic Leadership. Foundation & Recognition (1995–2006): Marked by the first successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in 1995, the establishment of the Laboratory of Stem Cell Research and Application (later VNUHCM-US Stem Cell Institute), and the issuance of Directive 50-CT/TW, which formally prioritized biotechnology development. Development & Validation (2006–2024): Characterized by robust preclinical research on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), including isolation, characterization, and expansion, alongside disease-specific models (e.g., diabetes, spinal cord injury, liver fibrosis). Regulatory milestones include AABB accreditation in 2023 and the Draft Amendment to the Law on Medical Examination and Treatment in 2025. Clinical Impact & Leadership (2024–2025): Highlights the expansion into over 20 clinical applications, including osteoarthritis, COPD, spinal cord injury, autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, and solid tumors. The phase culminates in the Prime Ministerial Decision in 2025 designating cell therapy as a National Strategic Technology, positioning Vietnam as a regional leader in the field.

The pioneering phase (1995 – 2005): Proof of Concept and Foundation Laying

This decade was defined by the initial demonstration of capability and the slow, deliberate building of expertise.

1995: The first milestone: The journey officially commenced with the first successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in Viet Nam, performed at the Blood Transfusion Hematology Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City for a 21-year-old male patient with acute myeloid leukemia5. Under the guidance of Professor Trần Văn Bé, this landmark procedure proved that complex cellular therapies were technically possible within the country’s healthcare infrastructure. The patient’s full recovery and return to normal life served as a powerful, tangible testament to the technology’s potential5.

Expanding technical mastery (1995-2005): Following this success, the focus was on consolidating HSCT expertise. Techniques evolved from bone marrow harvests to the use of peripheral blood stem cells, reducing invasiveness for donors. Major hospitals in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City began establishing their own transplant programs, primarily treating hematologic malignancies and genetic blood disorders like thalassemia. Each successful case solidified clinical protocols, trained multidisciplinary teams, and built the essential ecosystem of apheresis, cell processing, and specialized patient care 6,7.

The expansion and institutionalization phase (2005 – 2020): Research bloom and clinical diversification

A pivotal shift occurred around 2005, moving beyond HSCT to embrace the broader potential of regenerative medicine, fueled by top-down strategic support.

Policy Catalyst: The 2005 Directive 50-CT/TW from the Party Central Committee on biotechnology development formally recognized the strategic importance of fields like stem cell research. This provided a crucial political and motivational framework, encouraging investment and prioritization.

Birth of a Research Hub: In 2006, the Laboratory of Stem Cell Research and Application (SCL) (now VNUHCM-US Stem Cell Institute) was established under the University of Science, Viet Nam National University Ho Chi Minh City (VNU-HCM). As the first dedicated national stem cell research institution, its mission was threefold: fundamental research, human resource training, and serving as a national technology resource. Its creation signaled a deep institutional commitment to building indigenous scientific capacity.

Preclinical Research Focus: Vietnamese scientists began intensive preclinical work. The primary focus was on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), sourced from accessible tissues like umbilical cord8,9,10,11,12,13, umbilical cord blood14,15,16,17, adipose tissue18,19, dental pulp, and bone marrow12,20. Research in animal models targeted conditions of high local burden: osteoarthritis (cartilage repair)21,22, osteochondral femoral head defect23, spinal cord injury24, ischemia25,26,27,28, liver fibrosis29,30 and diabetes31,32,33,34. Parallel work explored immune cell therapies like natural killer (NK) cell expansion 35,36,37, laying groundwork for future applications.

Clinical translation beyond HSCT: This period saw the first clinical applications of MSC therapies. Driven by high prevalence, knee osteoarthritis became a major focus, with hospitals offering injections of adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction or cultured MSCs 38. In a world-leading regulatory move, the Ministry of Health officially approved a protocol for intravenous infusion of allogeneic umbilical cord-derived MSCs for COPD in 201639. Experimental applications for cerebral palsy40, autism41, and spinal cord injury42 also began under compassionate use or early-phase trials.

Ecosystem Growth: The number of licensed stem cell banks increased43, and professional networks like the Ho Chi Minh Stem Cell Society were formed, connecting experts across the country.

The strategic integration and quality leap phase (2020 – 2025): standardization and national recognition

The most recent phase is characterized by efforts to systematize, assure quality, and elevate cell therapy to a matter of national strategy.

Regulatory Strengthening: In 2020, Decision 4259/QD-BYT by the Ministry of Health established a more detailed regulatory system, creating a safer legal corridor for all activities from research to treatment. This was part of a push to replace earlier patchwork guidelines with a cohesive framework.

International quality validation: A transformative milestone was achieved when some stem cell banks received full accreditation for cellular therapy services from the AABB43. This independent, international certification validated that Vietnamese cell processing and handling could meet the highest global standards for quality, safety, and potency, building crucial trust with patients and partners worldwide.

Advanced therapy development: This period saw the maturation of sophisticated, home-grown therapies. Many clinical trials were approved and carried out in varous hospitals for various diseases. In this period, not only cellular therapy as stem cells or immune cells but also accelular therapy as exosomes and extracellular vesicles were used in clinic. Some clinical conditions could be used cell therapy included cancers44, injuries42,45,46,47, degenerative diseases48,49,50,51, chronic inflamation39,41,52, and aging53.

Peak National Recognition: The journey reached an apex in June 2025 with Prime Ministerial Decision 1131/QD-TTg, which formally listed cell therapy and regenerative medicine in the National Strategic Technology Portfolio. This designation unlocks prioritized policy support, investment, and development focus, marking the field’s transition from a promising medical specialty to a cornerstone of national scientific and economic ambition.

The preclinical and translational research foundation

The clinical applications realized today are built upon a sustained commitment to preclinical research, which served as the essential bridge between concept and clinic.

Institutional Drivers

The VNUHCM-US Stem Cell Institute has been the national flagship, but other key players include research groups at Hanoi Medical University, Military Medical University, and the Vinmec Research Institute of Stemcell and Gene Technology. These institutions focused on mastering core techniques: stem cell isolation, characterization, expansion, and differentiation. They also served as critical training grounds for a new generation of Vietnamese scientists.

Strategic research focus areas

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs): As the most active research area, work focused on optimizing isolation from Vietnamese donors, characterizing their paracrine (secretory) and immunomodulatory properties, and testing them in robust animal models for specific diseases (diabetes mellitus, spinal cord injury, liver chrorisis, myocardial injury …) 21,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,54,55,56,57. This targeted approach ensured research was relevant to domestic health needs.

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs): Preclinical research supported clinical HSCT programs by exploring ways to expand HSC numbers , improve engraftment, and better understand and prevent complications like graft-versus-host disease.

Immune cell therapies: Early work on NK cell biology and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) provided the foundation for AIET. More recently, exploratory research into CAR-T cell engineering has begun58,59,60,61,62,63, often reliant on international collaboration for access to viral vectors and gene-editing technologies.

The engine of international collaboration

Partnerships have been indispensable. Collaborations with Japanese, Korean, Singaporean and American institutions or companies facilitated technology transfer, researcher exchange, and access to advanced protocols. These partnerships integrated Vietnamese science into the global mainstream, accelerated the learning curve, and helped align local practices with international quality standards.

Clinical Translation: From transplantation to regeneration and immunotherapy

Vietnam’s clinical landscape in cell therapy is now diverse, spanning established lifesaving procedures, regenerative applications, and cutting-edge immuno-oncology.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: The established backbone

HSCT is now routine in major centers like the National Institute of Hematology and Blood Transfusion (NIHBT) in Hanoi and the Blood Transfusion Hematology Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City64. It is the standard of care for various leukemias, lymphomas, myelomas, aplastic anemia, and severe thalassemia. The maturation of these programs created the essential infrastructure (sterile labs, cryopreservation, clinical protocols) that later supported other cell therapies.

Mesenchymal stem cell therapies: Addressing chronic degeneration

Knee osteoarthritis: Intra-articular injection of autologous adipose-derived SVF or cultured MSCs is widely offered. Clinical reports note significant improvements in pain (VAS scores), function (WOMAC index), and cartilage quality on MRI, providing a regenerative alternative to pain management or joint replacement13,38,47.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): The MoH-approved protocol for allogeneic umbilical cord-derived MSCs represents a significant achievement. Treatment aims to modulate lung inflammation and fibrosis, with trials reporting improvements in lung function (FEV1) and quality of life39,65,66.

Neurological and Autoimmune Conditions: Smaller-scale studies and compassionate use programs for cerebral palsy40,67, autism spectrum disorder41, and spinal cord injury42 continue, focusing on safety and feasibility. Outcomes are monitored through functional and behavioral assessments, contributing to a growing repository of clinical experience.

Clinical applications of cell therapy in Viet Nam (2015-2025)

| Year | Disease/Condition | Type of cells | Type of source | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | COPD | UC-MSCs | Allogenic | |

| 2016 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | ADSC | Autologous | |

| 2016 | Type 2 diabese mellitus | Peripheral blood stem cells | Autologous | |

| 2017 | Knee osteoarthritis | SVF | Autologous | |

| 2017 | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | BM-MNC | Autologous | |

| 2017 | Cerebral palsy | BM-MNC | Autologous | |

| 2019 | Spinal cord injury | ADSC | Autologous | |

| 2019 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | BM-MNC | Autologous | |

| 2019 | Children with cerebral palsy related to neonatal icterus | BM-MNC | Autologous | |

| 2019 | Colon, liver, and lung cancer | NK and CTL | Autologous | |

| 2020 | COPD | UC-MSC | Allogenic | |

| 2020 | Knee osteoarthritis | BM-MNC | Autologous | |

| 2020 | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | UC-MSC | Allogenic | |

| 2021 | COPD | SVF | Autologous | |

| 2021 | Autism spectrum disorder | BM-MNC | Autologous | |

| 2021 | Traumatic brain injury | BM-MSC | Autologous | |

| 2021 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | BM-MSC | Autologous | |

| 2021 | Sexual Functional Deficiency | ASDC | Autologous | |

| 2021 | Decompensated cirrhosis | BM-MNC | Autologous | |

| 2021 | Non-small cell lung cancer | Gamm delta T | Autoglogous | |

| 2022 | Liver cirrhosis | BM-MNC | Autologous | |

| 2022 | Knee osteoarthritis | SVF | Autologous | |

| 2022 | Traumatic brain injury | MNC and MSC | Autologous | |

| 2023 | Chronic granulomatous disease | BM-MNC | Autologous | |

| 2024 | Knee osteoarthritis | UC-MSC | Allogenic | |

| 2024 | Inflamm-aging | ADSC | Autologous | |

| 2025 | Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome | BM-MNC/HSC | Allogenic | |

| 2025 | Biliary atresia | BM-MNC | Autologous | |

| 2025 | Traumatic brain injury | BM-MNC | Autologous | |

| Ongoing | Frailty | ADSC | Autologous | |

| Ongoing | Chronic inflammation in older people | UCMSC | Allogenic | |

| Ongoing | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Car-T CD19 | Autologous |

Autologous immune enhancement therapy (AIET)

AIET exemplifies Vietnam’s capacity for complex translational work. The process involves leukapheresis, followed by 2-3 weeks of activation and expansion of NK cells and T-cells using cytokines like IL-2, before reinfusion. Used as an adjuvant to surgery, chemo-, or radiotherapy for cancers (liver, lung, breast, colorectal), some reports showed that AIET with prolonged survival, reduced recurrence, and minimal side effects44,72,76. Its success demonstrates a viable model for adopting and adapting advanced personalized therapy.

The evolving regulatory and ethical ecosystem

The scientific and clinical advances have necessitated and driven the parallel development of a legal and ethical framework.

From Guidance to Law

For years, the field operated under general MoH regulations on medical treatment and biologicals, supplemented by specific guidelines like the "Guidance on the Application of Stem Cells in Treatment." This created ambiguities around sourcing, banking, and approval pathways. The 2020 Decision 4259/QD-BYT was a step towards systematization, introducing more detailed technical and administrative requirements.

The 2025 Inflection Point

The 2025 Draft Amendment to the Law on Medical Examination and Treatment proposes the most comprehensive legal framework to date, with dedicated stem cell provisions. Key elements include:

-

Clear legal definitions for stem cells, cell lines, and products.

-

Formal rules for tissue donation (e.g., umbilical cord) and the operation of stem cell banks.

-

Explicit prohibition on human embryo creation for research/therapy, aligning with international ethics.

-

Defined scopes of application for treatment. This draft, culminating in the 2025 Strategic Technology designation, reflects the state’s commitment to creating an enabling yet safe environment for the field’s sustainable growth.

Ethical navigation

The ethical discourse has matured alongside the science. Key issues include ensuring informed consent (especially for cord blood donation), protecting patients in early-phase trials against unrealistic expectations, and combating unverified “stem cell tourism” clinics. The proposed legal bans are a direct response to core ethical concerns, but ongoing professional and public education remains vital to foster a realistic understanding of benefits and risks.

Persistent challenges and strategic future perspectives

Despite monumental progress, significant hurdles remain to be overcome for sustainable and equitable growth.

Ongoing challenges

Regulatory finalization and implementation: The swift enactment and detailed implementation of the 2025 draft law and its subordinate decrees are paramount. Clear pathways for clinical trial approval, product classification, and market authorization are needed to attract serious investment.

Rigorous clinical trial culture: There is a need for more large-scale, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted to international standards (ICH-GCP) to generate robust efficacy data for local therapies. A 2025 study highlighted public willingness to participate in trials but also identified major barriers: concerns over risks and a general lack of knowledge, underscoring the need for public engagement.

Cost and accessibility: Advanced therapies like AIET and cultured MSC treatments remain expensive, confined largely to private hospitals. Developing sustainable financing models, exploring health insurance coverage, and scaling up production to reduce costs are critical for equitable access.

Human resources and technology: There is a continuous need for deep, specialized training for researchers, technicians, and clinicians. Investment in state-of-the-art, harmonized equipment and fostering basic research to develop home-grown intellectual property are also essential.

Long-term pharmacovigilance: Establishing national patient registries to track long-term outcomes and potential late effects of cell therapies is a necessary component of responsible medicine that requires development.

Strategic future pathways

From Recipient to partner in international collaboration: Vietnam can leverage its established networks to move into co-development partnerships for next-generation therapies (e.g., off-the-shelf MSC products, gene-edited cells).

Positioning as a regional hub: Combining clinical excellence (validated by AABB), innovative therapies (like AIET), and cost-effectiveness could establish Vietnam as a recognized destination for advanced cell therapy in Southeast Asia.

Leveraging domestic strengths: Deep knowledge in MSC biology and local disease epidemiology should drive investigator-initiated trials, potentially yielding unique therapeutic insights for regional health problems.

Building the complete pipeline: The ultimate goal is a seamlessly integrated ecosystem connecting basic research, GMP manufacturing, clinical trial centers, a national quality control body, and a responsive regulator to efficiently translate discovery into safe, effective, and accessible treatments.

Conclusion

Vietnam’s 30-year journey in cell therapy, from the "seemingly impossible" first transplant in 1995 to its recognition as a "National Strategic Technology" in 2025, is a narrative of remarkable vision, perseverance, and incremental achievement. It is a story that traverses the full spectrum of translational medicine: from foundational lab science to pioneering clinical trials, from ad hoc guidelines to comprehensive law, and from isolated procedures to an integrated national ecosystem.

Milestones such as the government-sanctioned use of MSCs for COPD, the development of the sophisticated AIET platform, and the coveted AABB accreditation demonstrate that Viet Nam is not merely a passive adopter of global technology but an active contributor, capable of meeting international standards and generating local innovation.

The path forward, while bright, is not without obstacles. The full potential of this field for the Vietnamese people depends on the finalization and effective implementation of a clear regulatory framework, a commitment to rigorous clinical science, and concerted efforts to make these breakthroughs accessible beyond the privileged few. By continuing to invest strategically in its human and physical infrastructure, foster ethical practice, and deepen both domestic integration and international partnership, Viet Nam is poised to solidify its role as a significant and innovative player in the dynamic landscape of 21st-century regenerative medicine and cell-based therapy, serving as an inspiring model for biomedical progress in the developing world.

Abbreviations

AABB: Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies; ADSC: Adipose-Derived Stem Cells; AIET: Autologous Immune Enhancement Therapy; BM-MNC: Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cells; BM-MSC: Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells; CAR-T: Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cells; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CTL: Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes; FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second; GMP: Good Manufacturing Practice; HSC: Hematopoietic Stem Cell; HSCs: Hematopoietic Stem Cells; HSCT: Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation; ICH-GCP: International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use - Good Clinical Practice; IL-2: Interleukin-2; MNC: Mononuclear Cells; MoH: Ministry of Health; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; MSCs: Mesenchymal Stem Cells; NIHBT: National Institute of Hematology and Blood Transfusion; NK cells: Natural Killer cells; RCTs: Randomized Controlled Trials; SCL: Stem Cell Research and Application Laboratory; SVF: Stromal Vascular Fraction; TILs: Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes; UC-MSC: Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; VNU-HCM: Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City; VNUHCM–US: Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City – University of Science; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; γδT: Gamma Delta T Cells

Acknowledgments

None.

Author’s contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that they have used generative AI and/or AI-assisted technologies in the writing process before submission, but only to improve the language and readability of their paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.