Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Transformative Frontier in Regenerative Medicine Navigating Promise and Challenges

- Stem Cell Research Centre, Telangana, India

Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have emerged as one of the most promising therapeutic tools in regenerative medicine over the past few decades. Initially identified for their capacity to differentiate into mesodermal lineages, these cells are now recognized for their profound immunomodulatory properties, trophic factor secretion, and homing capabilities to sites of injury. This commentary examines the evolution of MSC research from their initial discovery to current clinical applications, highlighting both the substantial progress made and the significant challenges that remain. While MSCs have demonstrated remarkable potential in treating conditions ranging from graft-versus-host disease to orthopedic injuries, issues of heterogeneity, manufacturing consistency, and variable clinical outcomes continue to complicate their widespread therapeutic adoption. The future of MSC-based therapies likely lies in standardized production protocols, advanced bioengineering approaches, and a refined understanding of their mechanisms of action, potentially unlocking their full clinical potential in the coming years.

Introduction

The field of regenerative medicine has witnessed unprecedented growth over the past three decades, with mesenchymal stem cells occupying a central role in both basic research and clinical translation. First identified in the bone marrow by Alexander Friedenstein in the 1960s and later named by Arnold Caplan in 1991, MSCs were initially characterized as plastic-adherent, fibroblast-like cells capable of differentiating into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages1. This narrow definition has substantially expanded over time, revealing cells with remarkable biological properties that extend far beyond simple differentiation capacity.

The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) established minimum criteria for defining MSCs, including: (1) adherence to plastic under standard culture conditions; (2) expression of specific surface markers (CD73, CD90, CD105) while lacking expression of hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45, CD14, CD19, HLA-DR); and (3) ability to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondroblasts 2. While these criteria provide important standardization, they capture only a fraction of the functional diversity that makes MSCs so therapeutically intriguing.

MSCs have since been isolated from virtually every vascularized tissue in the human body, including adipose tissue1,3,4, umbilical cord5,6, dental pulp 7, placenta 8, and synovial membrane 9,10. This ubiquitous distribution hints at their fundamental role in tissue homeostasis and repair. Unlike embryonic stem cells or induced pluripotent stem cells, MSCs avoid many ethical controversies while offering practical advantages for clinical use, including relative ease of isolation, expansion capabilities, and initially low immunogenicity.

The therapeutic appeal of MSCs has evolved considerably from their initial characterization as mere structural precursors. Contemporary understanding recognizes these cells as orchestrators of repair through complex paracrine signaling and immunomodulation rather than simply as building blocks for tissue regeneration 1,11,12,13. This paradigm shift has opened new avenues for clinical applications while simultaneously complicating the mechanistic understanding of how MSC therapies actually work. As we stand at the intersection of basic science and clinical translation, this commentary aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of MSC research, its clinical applications, persistent challenges, and future directions.

Biological Characteristics and Evolving Understanding of MSCs

Fundamental Properties

The functional versatility of MSCs stems from their unique biological characteristics. Unlike many adult stem cells with restricted differentiation potential, MSCs exhibit multipotent capacity, enabling them to generate various cell types including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, and potentially other lineages under appropriate conditions14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. This differentiation potential, combined with their capacity for self-renewal, forms the foundational rationale for their application in tissue regeneration.

Perhaps even more significant than their differentiation capacity is the remarkable immunomodulatory capability of MSCs. These cells can interact with both innate and adaptive immune systems, suppressing T-cell proliferation, modulating dendritic cell maturation, inhibiting B-cell activation, and inducing regulatory T-cells 22,23,24,25,26,27. This immunomodulation occurs through both cell-to-cell contact and secretion of soluble factors such as prostaglandin E2, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, transforming growth factor-β, and interleukin-1027,28,29. This property allows MSCs to exert potent anti-inflammatory effects, making them particularly valuable for treating autoimmune and inflammatory conditions.

Another critical feature of MSCs is their homing capability – the ability to migrate toward sites of inflammation, tissue injury, or tumors following systemic administration 30,31,32,33. This tropism is mediated by chemokine receptors and adhesion molecules that respond to signals released from damaged tissues. This intrinsic targeting system makes MSCs ideal vehicles for delivering therapeutic agents directly to pathological sites, a property increasingly exploited in drug delivery strategies 34,35,36.

Historical Evolution and Nomenclature Debate

The conceptualization of MSCs has undergone significant evolution since their initial discovery. Friedenstein's pioneering work in the 1960s and 1970s identified bone marrow stromal cells capable of forming bone and supporting hematopoiesis 1,37,38. The term "mesenchymal stem cell" was subsequently coined by Caplan in 1991, reflecting the presumed embryonic origin and stem-like properties 1,39. However, as research progressed, limitations in our understanding became apparent, leading to ongoing debates regarding nomenclature and biological identity.

Evolution of MSC Nomenclature and Understanding

| Time Period | Primary Concept | Key Findings | Therapeutic Emphasis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s-1980s | Stromal/osteogenic precursor | Friedenstein's CFU-Fs; bone formation in vivo | Tissue formation and regeneration |

| 1990s | Mesenchymal stem cell | Multilineage differentiation; surface markers | Cell replacement through differentiation |

| 2000s | Immunomodulatory cells | Suppression of immune responses; MHC expression | Treatment of autoimmune diseases and GvHD |

| 2010s-2024 | Medicinal signaling cells | Paracrine effects; extracellular vesicles; drug delivery | Trophic factor secretion; targeted delivery |

| 2024 | Master Signaling Cells | Cell signaling transduction | Trophic factor secretion; Cellular and conditioned medium therapy |

The appropriateness of the term "stem cell" has been questioned, as evidence for their self-renewal and multipotency remains limited compared to true stem cells like hematopoietic stem cells. This has led to proposals for alternative nomenclature, including "mesenchymal stromal cells" 39 or Caplan's more recent suggestion of "medicinal signaling cells" to better reflect their primary therapeutic mechanisms40. The naming controversy underscores fundamental questions about the true nature of these cells and their biological roles in homeostasis and repair.

Recent research has increasingly focused on the paracrine functions of MSCs rather than their differentiation capacity. Secreted factors and extracellular vesicles from MSCs contain various bioactive molecules – including growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and non-coding RNAs – that mediate most of their therapeutic effects. Therefore, according to Pham (2024), MSCs have been renamed as “master signaling cells”1.

This recognition has shifted therapeutic strategies toward using MSC-conditioned media or extracellular vesicles as cell-free alternatives, potentially offering similar benefits while avoiding risks associated with whole-cell transplantation41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50.

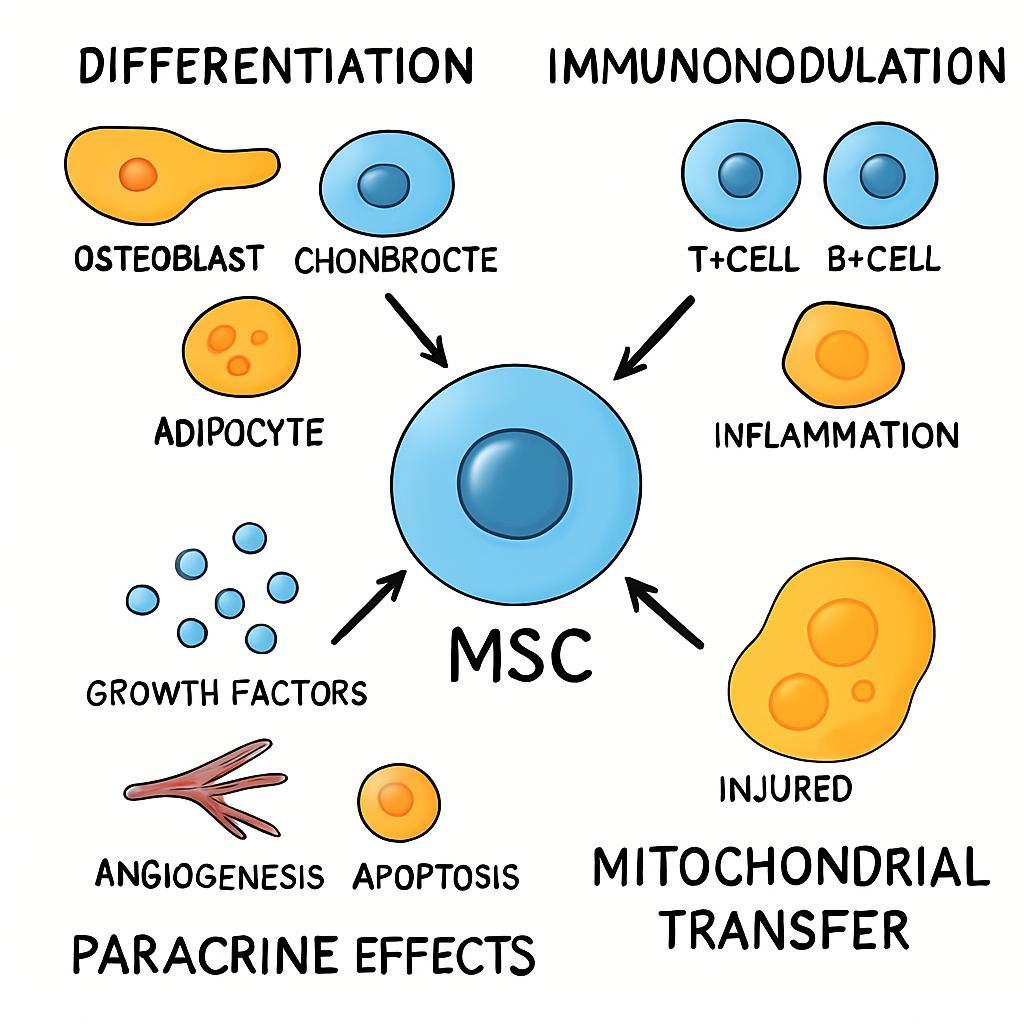

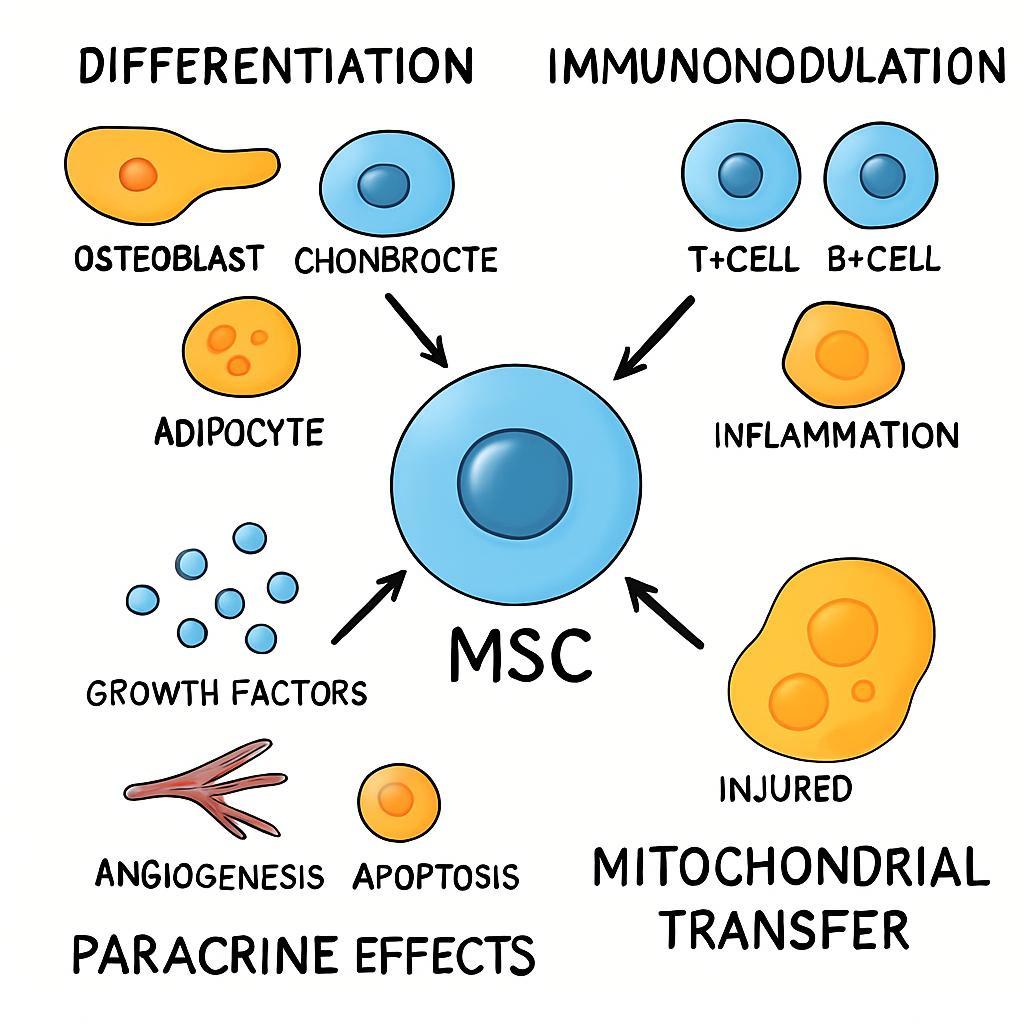

A Schematic Overview of the Primary Therapeutic Mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs). The figure highlights the multifaceted role of MSCs in regenerative medicine, which is driven by three interconnected mechanisms. (1) Direct Differentiation: Upon homing to sites of injury, MSCs can differentiate into site-specific lineages, directly contributing to tissue repair. (2) Immunomodulation: MSCs exert potent anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing pro-inflammatory immune responses and promoting a tolerogenic environment. (3) Paracrine Effects: A primary mechanism of action involves the secretion of trophic factors that orchestrate a complex healing response, including the promotion of angiogenesis (new blood vessel growth), inhibition of apoptosis (programmed cell death), and reduction of fibrosis (scar tissue). Together, these actions underscore the function of MSCs as orchestrators of tissue repair.

Therapeutic Mechanisms and Applications

Multimodal Mechanisms of Action

The therapeutic efficacy of MSCs derives from multiple interconnected mechanisms that operate in concert. The initial paradigm centered on direct differentiation, wherein MSCs were thought to engraft at injury sites and directly replace damaged tissues by differentiating into site-specific cell types. While this mechanism does contribute to their regenerative effects, particularly in orthopedic applications, it likely accounts for only a fraction of their therapeutic impact.

The immunomodulatory properties of MSCs represent perhaps their most clinically exploited mechanism. Through both contact-dependent and independent pathways, MSCs can suppress pro-inflammatory responses while promoting anti-inflammatory networks. This immunomodulation is not constitutive but requires "licensing" or activation by inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α present in disease microenvironments 51,52,53,54. This contextual activation provides a self-regulating therapeutic system that responds to disease severity.

The paracrine activity of MSCs has emerged as a central mediator of their therapeutic effects. MSCs secrete a diverse array of bioactive factors that promote angiogenesis, reduce apoptosis, inhibit fibrosis, and stimulate endogenous progenitor cells 55,56,57,58,59. These secretory properties are now recognized as primary mediators of tissue repair, leading to the exploration of MSC-derived extracellular vesicles as potential cell-free therapeutics. Additionally, MSCs can transfer mitochondria to injured cells, restoring cellular bioenergetics and enhancing survival 60,61,62.

Clinical Translation and Applications

MSCs have been investigated in over a thousand clinical trials spanning diverse conditions, with several areas showing particular promise:

-

Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD): MSCs have demonstrated significant efficacy in steroid-refractory acute GvHD, leading to the 2024 FDA approval of Ryoncil (remestemcel-L) for pediatric patients

63 . Their immunomodulatory capabilities help reestablish immune homeostasis without causing broad immunosuppression. -

Orthopedic applications: MSCs have shown promise in treating osteoarthritis, cartilage defects, and bone regeneration. Products like Cartistem® (umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs) have received regulatory approval in South Korea for degenerative osteoarthritis

64 . The combination of MSCs with appropriate scaffolds has advanced tissue engineering approaches for musculoskeletal repair. -

Neurological disorders: Early-phase trials have explored MSC therapy for conditions including multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, spinal cord injury, and stroke

65 ,66 ,67 . Benefits appear derived primarily through trophic support and immunomodulation rather than direct cell replacement. -

COVID-19 and ARDS: During the COVID-19 pandemic, MSCs were investigated for their ability to mitigate the cytokine storm and promote tissue repair in severe respiratory cases

68 ,69 ,70 ,71 . Their anti-inflammatory and regenerative properties showed potential in reducing mortality and improving recovery. -

Autoimmune diseases: Clinical trials have examined MSCs for Crohn's disease, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes, capitalizing on their ability to reset immune responses

72 ,73 ,74 .

Clinically Approved MSC-Based Products

| Product Name | Indication | Year Approved | Regulatory Agency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ryoncil | Pediatric steroid-refractory acute GvHD | 2024 | FDA (USA) |

| StemOne | Degenerative osteoarthritis | 2023 | CDSCO (India) |

| Cartistem | Degenerative osteoarthritis | 2011 | MFDS (South Korea) |

| HeartiCellgram | Myocardial infarction | 2011 | MFDS (South Korea) |

| Temcell | Acute GvHD | 2015 | PMDA (Japan) |

The translation of MSC therapies from bench to bedside illustrates both the promise and challenges of cell-based medicines. While numerous studies have demonstrated safety and modest efficacy, consistently robust outcomes across diverse patient populations remain elusive, highlighting the need for better understanding of MSC biology and refinement of therapeutic protocols.

Challenges and Controversies

Heterogeneity and Standardization Issues

Perhaps the most significant challenge in MSC therapeutics is their inherent heterogeneity. MSCs from different tissue sources, donors, and even within the same population exhibit substantial variation in their properties and functional capacities 75,76,77. Donor-specific factors including age, health status, and genetic background significantly influence MSC characteristics, creating challenges for reproducible therapy. For instance, MSCs from elderly or diabetic donors often show impaired proliferation and differentiation potential compared to those from young, healthy donors 78,79,80,81.

The lack of standardized protocols for isolation, expansion, and characterization further complicates clinical translation. Current good manufacturing practices (GMP) provide general guidelines, but specific details regarding culture conditions, passage numbers, and quality control metrics vary substantially between laboratories82,83. This methodological variability contributes to inconsistent clinical outcomes and difficulties comparing results across studies. The development of standardized, xenogen-free culture systems remains a critical need for advancing MSC therapies.

The functional characterization of MSCs presents additional challenges. While surface marker expression and differentiation capacity are routinely assessed, these parameters often correlate poorly with therapeutic efficacy84. More relevant potency assays that predict in vivo performance are urgently needed but have proven difficult to develop due to the multifactorial nature of MSC mechanisms85. This disconnect between characterization standards and functional potency represents a significant barrier to clinical advancement.

Safety Concerns and Clinical Limitations

Despite an overall favorable safety profile, MSC therapies present several important safety considerations. The potential for malignant transformation has been debated, with some animal studies suggesting possible tumor promotion though no confirmed cases of human MSC transformation 86. The risk appears particularly relevant in oncology contexts, where MSCs may integrate into tumor microenvironments and potentially support cancer progression through immunomodulation and stromal support87.

The immunogenicity of MSCs presents a complex safety consideration. While initially described as immune-privileged, it is now clear that MSCs can elicit immune responses, particularly after repeated administration or in certain inflammatory contexts 88. This secondary immunogenicity may limit long-term engraftment and efficacy, though it may not completely abrogate therapeutic effects mediated through transient paracrine activities.

Additional clinical challenges include poor engraftment and survival following transplantation. The hostile microenvironment of injured or inflamed tissues, characterized by hypoxia, oxidative stress, and inflammation, can rapidly decimate transplanted MSC populations 89. Some studies suggest that less than 1% of administered MSCs remain viable one week after transplantation90, raising questions about their mechanism of action and strategies for improving persistence.

The timing and route of administration also present clinical challenges. The optimal window for MSC therapy likely varies by indication, and the most effective delivery methods remain uncertain for many applications 91. Intravenous administration risks pulmonary sequestration, while local implantation may not provide adequate distribution92. These practical considerations significantly impact therapeutic efficacy but have received comparatively limited systematic investigation.

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

Emerging Strategies and Innovations

Several innovative approaches are being explored to overcome current limitations in MSC therapy:

-

Preconditioning and priming: Exposing MSCs to specific stimuli before administration can enhance their therapeutic properties. Preconditioning with hypoxia, inflammatory cytokines, or pharmacological agents can increase MSC survival, immunomodulatory capacity, and paracrine secretion

93 ,94 . For instance, interferon-γ priming upregulates indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression, enhancing immunosuppressive function. -

Genetic engineering: Modifying MSCs to overexpress therapeutic factors such as anti-apoptotic proteins, growth factors, or homing molecules can enhance their efficacy

95 ,96 . These engineered MSCs can serve as targeted delivery vehicles for therapeutic genes or proteins, particularly in oncology applications where their tumor-homing properties are advantageous. -

Biomaterial-assisted delivery: Combining MSCs with biomaterial scaffolds can improve retention, survival, and integration at target sites

97 ,98 . Three-dimensional culture systems and scaffold-free cell sheets better maintain MSC stemness and functionality compared to traditional two-dimensional culture. -

iPSC-derived MSCs: MSCs generated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) offer advantages in scalability, consistency, and quality control compared to primary MSCs

99 ,100 ,101 . These iMSCs represent a potentially unlimited, standardized cell source that could address heterogeneity issues. -

Extracellular vesicles and cell-free approaches: MSC-derived extracellular vesicles carry therapeutic cargo without the risks of whole-cell transplantation

102 ,103 . These nanoscale vesicles can be engineered for enhanced targeting and drug delivery, representing a promising cell-free alternative.

Regulatory and Manufacturing Evolution

The regulatory landscape for MSC therapies continues to evolve as these products demonstrate clinical potential. The designation of MSCs as Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) in many jurisdictions has established stringent requirements for their manufacturing and quality control 104,105. The recent FDA approval of Ryoncil represents a significant milestone, providing a regulatory pathway for future MSC-based products 106.

Advanced manufacturing technologies including closed-system bioreactors, automated processing, and rigorous potency assays are being implemented to enhance product consistency 107,108,109. The development of potency markers that reliably predict therapeutic efficacy remains a critical need for quality assurance and lot release. Additionally, the implementation of design-of-experiment approaches to manufacturing optimization can help identify critical process parameters that influence product quality.

Concluding Perspective

Mesenchymal stem cells have journeyed from curious laboratory observations to promising therapeutic agents with diverse clinical applications. Their evolution from simple structural precursors to complex medicinal signaling cells reflects our growing appreciation of their sophisticated biology. While significant challenges remain in standardization, manufacturing, and clinical implementation, the continued refinement of MSC-based therapies holds tremendous promise for regenerative medicine.

The future of MSC therapeutics likely lies not in a one-size-fits-all approach but in tailored strategies that match specific cell sources, preparation methods, and administration protocols to particular clinical indications. As our understanding of MSC biology deepens and manufacturing technologies advance, these remarkable cells are poised to make increasingly significant contributions to treating currently intractable diseases. Their unique combination of regenerative capacity, immunomodulation, and targeted delivery potential positions MSCs as versatile therapeutic tools that will continue to shape the landscape of regenerative medicine for years to come.

The road from laboratory discovery to widespread clinical implementation has been longer and more complex than initially anticipated, but the substantial progress made to date provides solid foundation for optimism. With continued rigorous science, thoughtful clinical trial design, and innovative approaches to overcoming current limitations, MSC-based therapies may yet fulfill their potential to transform treatment paradigms across numerous medical specialties.

Abbreviations

2D: Two-Dimensional; 3D: Three-Dimensional; ARDS: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome; ATMPs: Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products; CFU-Fs: Colony-Forming Units-Fibroblastic; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; FDA: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; GMP: Good Manufacturing Practices; GvHD: Graft-versus-host disease; HLA-DR: Human Leukocyte Antigen – DR isotype; IDO: Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase; IL-10: Interleukin-10; iMSCs: Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-derived Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells; iPSCs: Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells; ISCT: International Society for Cellular Therapy; MHC: Major Histocompatibility Complex; MSCs: Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells; PGE2: Prostaglandin E2; TGF-β: Transforming Growth Factor-β.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author’s contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that they have used generative AI and/or AI-assisted technologies in the writing process before submission, but only to improve the language and readability of their paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.