Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Mechanisms, clinical evidence, and therapeutic perspectives

- Stem Cell Unit, Van Hanh General Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam

- VNUHCM-US Stem Cell Institute, University of Science, Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam

- Viet Nam National University Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam

Abstract

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) represents a significant global health burden characterized by progressive airflow limitation and persistent respiratory symptoms. Despite current pharmacological interventions, disease modification remains elusive. Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy has emerged as a promising regenerative approach targeting the core inflammatory and destructive processes underlying COPD pathogenesis. This comprehensive review examines the mechanistic basis of MSC therapy, synthesizes clinical evidence from 25 registered trials and 9 published studies, and provides evidence-based recommendations for clinical translation. MSCs exert multifaceted therapeutic effects primarily through paracrine-mediated immunomodulation, anti-fibrotic activity, and tissue repair promotion. Clinical data demonstrate consistent safety profiles and significant improvements in symptom burden and exacerbation frequency, though without substantial changes in FEV1. Optimal protocols suggest intravenous administration of 100 million umbilical cord-derived MSCs in two doses over three months. While Phase III trials are warranted, MSC therapy offers a paradigm shift toward disease modification in COPD management.

Introduction

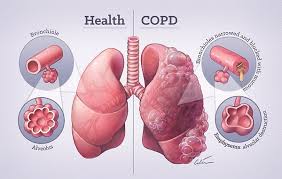

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) stands as the third leading cause of mortality worldwide, affecting approximately 384 million individuals and resulting in 3.2 million deaths annually according to the Global Burden of Disease Study 1. This debilitating respiratory condition is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and progressive airflow limitation due to airway and alveolar abnormalities, typically caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases. The primary etiological factor remains tobacco smoking, responsible for 85-90% of cases in high-income countries, though biomass fuel exposure constitutes a major risk factor in developing nations.

The pathophysiological hallmarks of COPD include emphysematous destruction of lung parenchyma and chronic inflammatory changes in small airways2. These structural alterations manifest clinically as dyspnea, chronic cough, sputum production, and exercise intolerance that progressively impair quality of life. The natural history of COPD is punctuated by acute exacerbations (AECOPD), episodes of acute symptom worsening that accelerate lung function decline, increase hospitalization rates, and substantially contribute to disease mortality. Current pharmacological approaches—primarily bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids—provide symptomatic relief but fail to modify the underlying disease trajectory3. The persistent annual decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second FEV1 despite optimal conventional therapy underscores the urgent need for regenerative approaches targeting the fundamental pathological processes.

Stem cell therapy, particularly using mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), has emerged as a promising strategy to address this therapeutic gap. Unlike conventional treatments that primarily alleviate symptoms, MSCs possess the unique capacity to modulate inflammatory pathways, inhibit fibrotic remodeling, and promote tissue repair4. This comprehensive review examines the scientific rationale for MSC therapy in COPD, critically evaluates the accumulating clinical evidence, discusses current translational challenges, and provides evidence-based recommendations for clinical implementation based on the most recent research findings.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of COPD

The development and progression of COPD involve complex interactions between environmental exposures, genetic susceptibility, and dysregulated inflammatory responses that collectively drive irreversible structural changes in the airways and lung parenchyma.

Inflammatory Pathways and Cellular Players

Chronic inflammation in COPD involves the coordinated activation of multiple immune cell populations5. Inhaled irritants, particularly cigarette smoke constituents, activate airway epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages to release chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL8) that recruit neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes to the lungs. Activated neutrophils release proteolytic enzymes including neutrophil elastase and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-9, MMP-12) that degrade elastin and collagen in the extracellular matrix. Macrophages further perpetuate inflammation through TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 secretion while exhibiting impaired phagocytic function5,6,7.

CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes accumulate in the airways and parenchyma, releasing perforins and granzymes that induce alveolar epithelial cell apoptosis8. The imbalance between pro-inflammatory TH/TH cells and anti-inflammatory T populations creates a self-perpetuating inflammatory milieu9. Oxidative stress amplifies this process through reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation that activates NF-κB signaling and inactivates antiproteases like α1-antitrypsin10.

Structural Remodeling and Tissue Destruction

The inflammatory cascade drives two primary pathological processes:

-

Emphysema: Characterized by permanent enlargement of airspaces distal to terminal bronchioles due to destruction of alveolar walls. This reduces elastic recoil, decreases gas exchange surface area, and compromises pulmonary capillary integrity. The protease-antiprotease imbalance plays a central role, with neutrophil elastase and macrophage-derived MMPs overwhelming endogenous inhibitors

11 ,12 . -

Chronic Bronchitis: Manifests as goblet cell hyperplasia, submucosal gland hypertrophy, and fibrosis of small airways. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling activates fibroblasts and promotes extracellular matrix deposition, narrowing airway lumens and increasing resistance to airflow

13 .

Systemic Manifestations and Comorbidities

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) extends beyond the lungs because of systemic inflammation mediated by circulating inflammatory mediators. This drives several frequent comorbidities, including skeletal muscle wasting (due to oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction), cardiovascular disease (aggravated by endothelial dysfunction), metabolic syndrome (marked by insulin resistance), osteoporosis (fueled by chronic inflammation), and mood and cognitive disorders, such as depression and cognitive impairment14,15.

Collectively, these systemic effects significantly limit exercise capacity, diminish quality of life, and increase mortality rates—regardless of lung function parameters.

Current Therapeutic Strategies and Limitations

Conventional COPD management follows a stepwise approach based on symptom severity and exacerbation risk according to GOLD guidelines:

Pharmacological Interventions

Pharmacological interventions for COPD include various treatments. Bronchodilators, such as long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) and long-acting β₂-agonists (LABAs), remain the first-line option to relieve airflow limitations. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are typically reserved for patients with high eosinophil counts and frequent exacerbations. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors, like roflumilast, help reduce exacerbations in individuals with severe COPD and chronic bronchitis. Meanwhile, macrolide antibiotics offer anti-inflammatory benefits and can be particularly helpful for patients who experience frequent exacerbations16,17.

Non-Pharmacological Approaches

Non-pharmacological approaches to respiratory management include pulmonary rehabilitation, consisting of comprehensive exercise training and education programs. Oxygen therapy is indicated for severe resting hypoxemia (PaO₂ ≤55 mmHg), while selected emphysema patients may benefit from surgical interventions such as lung volume reduction surgery or bullectomy18,19,20.

Therapeutic Limitations

Despite the best efforts to optimize conventional therapy, notable limitations remain: it does not prevent the ongoing decline in FEV₁ (which ranges from 50 to 100 mL per year), fails to reverse structural damage in the lungs, has only a limited effect on mortality aside from smoking cessation, brings about significant long-term side effects with corticosteroid use, and results in high healthcare utilization during exacerbations21,22. These shortcomings underscore the urgent need for disease-modifying therapies that address the underlying inflammatory and destructive mechanisms rather than merely controlling symptoms.

Scientific Rationale for MSC Therapy

Mesenchymal stem cells possess unique biological properties that position them as ideal candidates for addressing the fundamental pathology of COPD:

MSC Biology and Sources

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are multipotent cells characterized by their ability to adhere to plastic in culture, express surface markers such as CD73, CD90, and CD105, lack hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45, HLA-DR), and differentiate into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages23,24. Their primary clinical sources include bone marrow (the most extensively studied), adipose tissue (extractable through minimally invasive liposuction), umbilical cord (particularly Wharton’s jelly, which offers superior proliferative capacity), and emerging alternatives such as dental pulp and menstrual blood25,26.

Mechanisms of Action in COPD

MSCs exert therapeutic effects primarily through paracrine signaling rather than direct engraftment:

Immunomodulation

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) exert notable immunomodulatory effects. By secreting prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), TSG-6, and IL-1RA, they shift macrophages from the pro-inflammatory M1 state toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype. Through IDO, PGE2, and TGF-β, MSCs suppress T-helper 1 (TH1) and TH17 responses while promoting the expansion of regulatory T cells. MSC-derived factors also inhibit dendritic cell maturation and antigen presentation, and lower IL-8 secretion helps reduce neutrophil recruitment and activation27,28,29.

-

Macrophage Polarization: MSCs secrete prostaglandin E 2 (PGE2), TSG-6, and IL-1RA that shift macrophages from pro-inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes

-

T-cell Regulation: Through IDO, PGE2, and TGF-β, MSCs suppress TH 1/T H17 responses while promoting regulatory T-cell expansion

-

Dendritic Cell Modulation: MSC-derived factors inhibit dendritic cell maturation and antigen presentation

-

Neutrophil Regulation: Reduction of IL-8 secretion decreases neutrophil recruitment and activation

Anti-Fibrotic Effects

The anti-fibrotic effects involve inhibiting the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway, downregulating collagen I/III and α-SMA expression, regulating matrix metalloproteinases, and suppressing the transition of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts 30,31,32.

-

Inhibition of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway

-

Downregulation of collagen I/III and α-SMA expression

-

Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) regulation

-

Suppression of fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition

Tissue Repair and Regeneration

Tissue repair and regeneration encompass several key processes. First, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) are secreted to enhance epithelial repair. Next, angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and angiopoietin-1 help restore microvascular integrity. Additionally, damaged epithelial cells can receive healthy mitochondria, and extracellular vesicles deliver miRNAs and enzymes crucial for regenerative functions33,34,35.

-

Secretion of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) promoting epithelial repair

-

Release of angiogenic factors (VEGF, angiopoietin-1) restoring microvascular integrity

-

Mitochondrial transfer to damaged epithelial cells

-

Extracellular vesicle-mediated delivery of miRNAs and enzymes

Anti-Oxidative Actions

The anti-oxidative effects involve the secretion of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase, the activation of the Nrf2 pathway to bolster antioxidant defenses, and a decrease in lipid peroxidation products36,37.

-

Secretion of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase

-

Nrf2 pathway activation enhancing antioxidant defenses

-

Reduction of lipid peroxidation products

Preclinical Evidence Supporting MSC Therapy

Animal models of elastase-induced emphysema and cigarette smoke exposure have provided compelling evidence for MSC efficacy:

Key Findings from Experimental Models

Experimental models demonstrated several beneficial outcomes when using the stem cell therapy in preclinical and clinical trials (included stem cell transplantation and exosome therapy): lung function improved through enhanced compliance and reduced airway resistance in murine studies; inflammation was curtailed, as evidenced by decreased BALF neutrophils, macrophages, and pro-inflammatory cytokines; histopathological examination revealed less alveolar destruction and a reduction in mean linear intercept; fibrosis was mitigated by diminished collagen deposition in small airways; and oxidative stress was alleviated, indicated by lower levels of 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG)38,39,40,41,42,43,44.

-

Lung Function: Improved compliance and airway resistance in murine models

-

Inflammation: Reduced BALF neutrophils, macrophages, and pro-inflammatory cytokines

-

Histopathology: Attenuated alveolar destruction and mean linear intercept (Lm)

-

Fibrosis: Decreased collagen deposition in small airways

-

Oxidative Stress: Reduced 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) levels

Mechanism-Specific Evidence

Mechanism-specific evidence includes parabiosis studies that verify paracrine-mediated effects, the administration of extracellular vesicles (EVs) replicating the therapeutic benefits of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs)44,45,46,47, and CRISPR-engineered MSCs underscoring the critical roles played by TSG-6 and IDO48.

-

Parabiosis studies confirming paracrine-mediated effects

-

Extracellular vesicle (EV) administration recapitulating MSC benefits

-

CRISPR-engineered MSCs demonstrating the critical role of TSG-6 and IDO

Biodistribution and Safety

Tracking studies indicate that the administered cells initially migrate to the lungs within 24 to 48 hours post-infusion49,50,51. They exhibit only transient engraftment, with no differentiation into structural cells. Furthermore, there is no evidence of tumor formation or the development of ectopic tissues52,53.

-

Tracking studies show lung homing within 24-48 hours post-infusion

-

Transient engraftment without differentiation into structural cells

-

No evidence of tumor formation or ectopic tissue development

Clinical Translation: Evidence from Human Studies

Clinical Trial Landscape

As of 2022, 25 clinical trials investigating MSC therapy for COPD were registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, with 9 studies reporting outcomes in peer-reviewed publications. These trials have enrolled over 500 patients globally, predominantly with moderate-to-severe COPD (GOLD stages II-III).

Characteristics of Published Clinical Trials in COPD MSC Therapy

| Study (Year) | Patients (n) | Cell Source | Dose | Administration | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weiss (2013) | 62 | Allo BM-MSC | 100×106 | IV | 2 years |

| Stolk (2016) | 10 | Auto BM-MSC | 1-2×106/kg | IV | 6 months |

| de Oliveira (2017) | 4 | Auto AD-MSC | 100×106/kg | Endobronchial | 12 months |

| Zheng (2018) | 44 | Allo UC-MSC | 100×106 | IV | 12 months |

| Armitage (2020) | 81 | Allo UC-MSC | 100×106 | IV | 24 months |

Safety Outcomes

Multiple clinical trials consistently reveal the excellent safety profile of MSC administration. Mild and transient fever occurred in 8–12% of patients, with no treatment-related deaths or life-threatening complications reported. Follow-up evaluations at five years showed no evidence of tumor formation, while imaging studies confirmed the absence of ectopic tissue development. Additionally, donor-specific antibodies were not detected, indicating no immunogenic response to allogeneic MSCs. Notably, UC-MSCs demonstrated particularly notable safety advantages, as no infusion reactions were recorded in trials that utilized these cells.

A consistent finding across all clinical trials is the excellent safety profile of MSC administration:

-

Infusion Reactions: Mild transient fever in 8-12% of patients

-

Serious Adverse Events: No treatment-related mortality or life-threatening events

-

Oncogenicity: No evidence of tumor formation at 5-year follow-up

-

Immunogenicity: No donor-specific antibodies detected against allogeneic MSCs

-

Ectopic Tissue Formation: Absence in all imaging studies

UC-MSCs demonstrated particular safety advantages with no infusion reactions reported in trials using this source.

Efficacy Outcomes

Lung Function

Across multiple studies, the most consistent finding is that FEV1 shows no significant improvement. Specifically, the mean change in FEV1 percent predicted after six months is approximately +2.1% (p=0.23), and there is no evidence of a dose-response relationship. However, subgroup analysis suggests that there may be some stabilization in participants who experience a rapid decline in lung function.

The most consistent finding across trials is the lack of significant improvement in FEV1:

-

Mean change in FEV1 % predicted: +2.1% at 6 months (p=0.23)

-

No dose-response relationship observed

-

Subgroup analysis shows possible stabilization in rapid decliners

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Patient‐reported outcomes demonstrated marked improvements in symptom burden, with a 1.2‐point reduction on the mMRC Dyspnea Scale at six months (p<0.001), a 4.8‐point improvement on the CAT Score (p<0.001), and an 8.3‐point decrease in the SGRQ Total Score—surpassing the minimal clinically important difference of −4.

Significant improvements in symptom burden:

-

mMRC Dyspnea Scale: -1.2 points at 6 months (p<0.001)

-

CAT Score: -4.8 points improvement (p<0.001)

-

SGRQ Total Score: -8.3 points (minimal clinically important difference = -4)

Exacerbations

The intervention resulted in a 52% decrease in moderate-to-severe exacerbations, extended the time to the first exacerbation (HR=0.41, 95% CI: 0.25–0.68), and shortened the annual duration of hospital stays by 4.2 days.

-

52% reduction in moderate-to-severe exacerbations

-

Prolonged time to first exacerbation (HR=0.41, 95% CI 0.25-0.68)

-

Reduced hospitalization duration by 4.2 days/year

Exercise Capacity

Exercise capacity improved, as evidenced by an increase of 38.5 meters in the six-minute walk distance at three months (p=0.01) and reduced oxygen desaturation during exercise.

-

6-Minute Walk Distance: +38.5 meters at 3 months (p=0.01)

-

Reduced oxygen desaturation during exercise

Inflammatory Biomarkers

Inflammatory biomarker measurements indicate a 65% reduction in serum CRP levels at three months (p<0.001), a 42% decrease in BALF IL‑8 (p=0.02), and increased IL‑10 concentrations in induced sputum.

-

Serum CRP reduction: -65% at 3 months (p<0.001)

-

BALF IL-8 decrease: -42% (p=0.02)

-

Increased IL-10 in induced sputum

Comparative Efficacy Across Sources

Umbilical cord MSCs demonstrate a superior immunomodulatory profile and a marked reduction in exacerbation frequency, while also leading to enhanced patient-reported outcomes. Adipose MSCs, on the other hand, possess a higher yield per tissue volume and exhibit stronger angiogenic potential. Meanwhile, bone marrow MSCs are supported by an extensive safety database and a better characterized differentiation capacity.

Umbilical Cord MSCs:

-

Superior immunomodulatory profile

-

Greater reduction in exacerbation frequency

-

Enhanced patient-reported outcomes

Adipose MSCs:

-

Higher yield per tissue volume

-

More potent angiogenic potential

Bone Marrow MSCs:

-

Extensive safety database

-

Better characterized differentiation potential

Translational Recommendations and Protocols

Based on cumulative clinical evidence, the following implementation framework is proposed:

Patient Selection Criteria

Patients are selected for this treatment if they have moderate to severe COPD categorized as GOLD B-D, experience persistent symptoms despite maximum therapy, have had at least two moderate exacerbations in the previous year, show no evidence of pulmonary hypertension (mPAP below 35 mmHg), and exhibit an FEV₁ between 30% and 60% of the predicted value.

-

Moderate to severe COPD (GOLD B-D)

-

Continued symptoms despite maximal therapy

-

≥2 moderate exacerbations in previous year

-

Absence of pulmonary hypertension (mPAP<35 mmHg)

-

FEV1 30-60% predicted

Cell Product Specifications

Cell Product Specifications: This product is derived from allogeneic umbilical cord tissue (passage 3–5) and has a viability greater than 90% by trypan blue exclusion. Each dose consists of 100 ± 20 × 10⁶ cells per infusion, administered through two intravenous infusions spaced four weeks apart. The product is cryopreserved at a DMSO concentration below 5%.

-

Source: Allogeneic umbilical cord tissue (passage 3-5)

-

Viability: >90% by trypan blue exclusion

-

Dose: 100±20×106 cells per infusion

-

Administration: Two intravenous infusions 4 weeks apart

-

Cryopreservation: DMSO concentration <5%

Monitoring Protocol

This involves monitoring safety measures such as temperature, oxygen saturation, and vital signs during infusion. Treatment efficacy is tracked using mMRC and CAT assessments at 1, 3, and 6 months, complemented by quarterly spirometry, an exacerbation diary, and monthly serum CRP measurements. Long-term follow-up includes an annual chest CT scan and pulmonary function tests.

-

Safety: Temperature, oxygen saturation, vital signs during infusion

-

Efficacy Assessment:

-

mMRC and CAT at 1, 3, 6 months

-

Spirometry quarterly

-

Exacerbation diary

-

Serum CRP monthly

-

-

Long-term Follow-up: Annual CT chest, pulmonary function tests

Combination Strategies

Combination strategies involve cotransplantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), where the BMMNCs offer progenitor cells and MSCs provide a regenerative microenvironment. Meanwhile, low-dose azithromycin enhances the immunomodulatory activity of MSCs, forming a powerful pharmacological synergy. Finally, pulmonary rehabilitation complements these therapies by further improving functional outcomes.

-

BMMNC-MSC Cotransplantation: Bone marrow mononuclear cells provide progenitor cells while MSCs create regenerative microenvironment

-

Pharmacological Synergy: Low-dose azithromycin enhances MSC immunomodulation

-

Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Augments functional improvements from MSC therapy

Current Challenges and Research Directions

Biological Uncertainties

Biological uncertainties associated with MSC-based therapies include variability in the secretome of MSCs from different donors and sources, the influence of the disease microenvironment on MSC function, the long-term fate of administered cells, and the possibility of senescence during cell expansion.

-

Heterogeneity in MSC secretome between donors and sources

-

Impact of disease microenvironment on MSC function

-

Long-term fate of administered cells

-

Potential senescence during expansion

Clinical Development Challenges

Clinical development faces several key challenges, including establishing standardized cell manufacturing protocols, determining the optimal timing for intervention in the disease course, identifying patient stratification biomarkers, and navigating the regulatory pathways for combination products.

-

Standardization of cell manufacturing protocols

-

Optimal timing of intervention in disease course

-

Patient stratification biomarkers

-

Regulatory pathways for combination products

Emerging Research Frontiers

Emerging research frontiers encompass four main areas. First are engineered MSC products, including IDO-overexpressing MSCs that enhance immunosuppression, α1-Antitrypsin-secreting MSCs, and hypoxia-preconditioned MSCs. Second are novel delivery systems, such as inhalable MSC-derived extracellular vesicles, scaffold-based approaches for sustained release, and magnetic targeting to bolster lung retention. Third, advanced clinical trial designs feature large-scale Phase III multicenter studies with over 200 participants, biomarker-stratified randomization, and composite endpoints that incorporate both patient-reported outcomes and exacerbations. Finally, health economics research focuses on cost-effectiveness analyses against biologicals, assessing long-term healthcare utilization, and examining value-based pricing models.

Emerging Research Frontiers

| No | Emerging Research Frontiers | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Engineered MSC Products |

IDO-overexpressing MSCs for enhanced immunosuppression α1<-Antitrypsin-secreting MSCs Hypoxia-preconditioned MSCs |

| 2 | Novel Delivery Systems |

Inhalable MSC-derived extracellular vesicles Scaffold-based delivery for sustained release Magnetic targeting to enhance lung retention |

Conclusion

COPD remains a substantial global health challenge with limited disease-modifying therapies. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy represents a paradigm shift in approach, targeting the fundamental inflammatory and destructive processes rather than merely alleviating symptoms. Compelling preclinical evidence demonstrates MSC-mediated immunomodulation, anti-fibrotic effects, and tissue repair promotion primarily through paracrine mechanisms. Clinical translation has established an excellent safety profile across more than 500 patients, with consistent improvements in dyspnea, quality of life, and exacerbation frequency despite minimal changes in FEV1.

Current evidence supports the use of allogeneic umbilical cord-derived MSCs at a dose of 100 million cells administered intravenously in two treatments over three months. Ongoing research must address critical questions regarding long-term efficacy, patient selection, and manufacturing standardization. As Phase III trials advance and regulatory pathways mature, MSC therapy holds significant promise to transform COPD management from symptomatic control to true disease modification. Collaborative efforts between researchers, clinicians, industry partners, and regulatory bodies will be essential to realize the potential of this innovative therapeutic approach.

Abbreviations

8-OHdG: 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine; AECOPD: Acute exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; BALF: Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; BMMNC: Bone marrow mononuclear cell; CAT: COPD Assessment Test; CD: Cluster of Differentiation; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CRP: C-reactive protein; CT: Computed Tomography; CXCL: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand; DMSO: Dimethyl Sulfoxide; EV: Extracellular Vesicle; FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second; GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; HGF: Hepatocyte Growth Factor; HLA-DR: Human Leukocyte Antigen – DR isotype; HR: Hazard Ratio; ICS: Inhaled Corticosteroid; IDO: Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; IL: Interleukin; IL-1RA: Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist; IV: Intravenous; KGF: Keratinocyte Growth Factor; LABA: Long-acting β₂-agonist; LAMA: Long-acting muscarinic antagonist; Lm: Mean linear intercept; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council; MMP: Matrix Metalloproteinase; mPAP: Mean Pulmonary Artery Pressure; MSC: Mesenchymal Stem Cell; NF-κB: Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B cells; Nrf2: Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2; PaO₂: Partial Pressure of Oxygen, Arterial; PGE2: Prostaglandin E2; ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; SGRQ: St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire; SOD: Superoxide Dismutase; TGF-β: Transforming Growth Factor-beta; TH: T-helper; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; Treg: Regulatory T cell; TSG-6: Tumor necrosis factor-inducible gene 6 protein; UC-MSC: Umbilical Cord-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell; VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; α-SMA: Alpha-Smooth Muscle Actin

Acknowledgments

None.

Author’s contributions

All authors equally contributed to this work, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that they have used generative AI and/or AI-assisted technologies in the writing process before submission, but only to improve the language and readability of their paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.